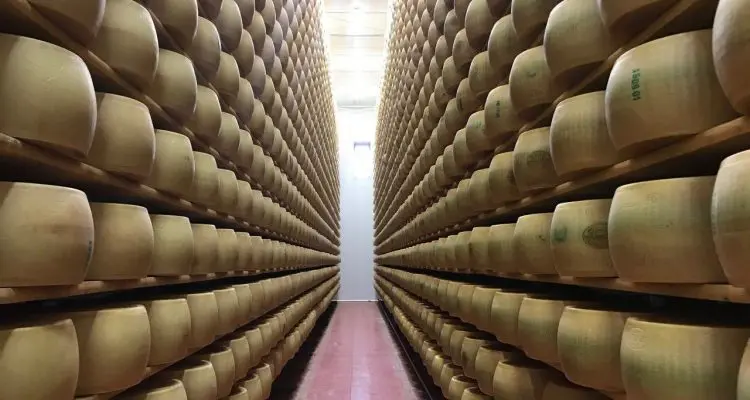

Italy is a land of tremendous variety, from dialects to architecture to hand gestures, and nowhere is this diversity more clear than in the country’s food and culinary traditions. Italy may be ancient, but the country is quite young, having only unified in 1861 (sans Rome, which forcibly joined in 1871). As a result, each region still retains its own distinct traditions, from foods to dialects. Italy boasts more foodstuffs (such as Parmigiano-Reggiano, pictured above) on the EU’s protected status list than any other country, with around 20% of the registrations coming from the land of the dolce vita. While friendly, Italians can be a bit judgemental at meals. Try and put ketchup on your pasta and the (metaphorical, hopefully) knives come out. When it comes to food, here are some near-universal traditions our Italian team felt would be especially good to know at the table.

Pasta pairings and how to eat spaghetti

Different types of pasta found in different regions are paired with specific sauces. The fresh egg pasta found in northern Italy’s Piedmont and Emilia Romagna regions is often served with butter sauce to bring out its subtle, refined flavor. Tomato sauce is associated with the south, while carbonara is more common in Central Italy, Genoa is known for pesto, and Bolognese sauce really does come from Bologna. Thick whole-wheat Bigoli pasta, one of Venice’s signature dishes, is flavored with onions and salty anchovies. Sicilians combine Busiate (long macaroni) with a pesto containing garlic and walnuts, or another type of pesto focusing on almonds, tomatoes, garlic, and basil. Some pasta dishes can be enhanced by adding some grated Parmigiano Reggiano or Grana Padana. When this is the case, the grated cheese will be offered or made available to you. When it isn’t, in the case of a seafood pasta (or risotto) it won’t be. If you request some cheese for your seafood, expect disapproving looks from the waiter and anyone else in earshot. Finally, when eating spaghetti, Italians skip the spoon — a fork suffices!

Sweet breakfast and coffee etiquette

Breakfast is generally sweet. Typically a ‘cornetto’ or ‘brioche’ (regional variations on a sweet croissant, with either a jam or nutella-like filling). Fittingly, cappuccino is only supposed to be consumed before noon. Italians are careful to only drink coffee after a meal (sometimes followed by a digestif). Milky coffees are frowned upon after breakfast. Incidentally when having a coffee out and about, particularly in touristy spots, you’ll often find there are two prices on a menu, one for ‘al banco’ (at the bar) and another for ‘a tavola’ (at the table). When you’re sitting down on a popular square for a coffee you are paying for much more than just the coffee. Effectively you’re renting that chair and table for a time.

A full buffet of food proverbs

Food’s prime importance in Italian life is echoed in its proverbs. Favorites include, “He who eats alone suffocates,” and, “At the table, one never ages.” Rather than an apple a day, Italians state, “Two drops of wine, and we can kick the doctor out the door.” Instead of having their cake and eating it too, Italians sadly “can’t have a full wine barrel and a drunken wife.” If you eat well, you’ll end up “as full as an egg,” but if you insult someone, make sure they don’t “make meatballs of you!”

Food crimes and bad luck

It shouldn’t need to be said, but just in case… Don’t ask for Hawaiian pizza, especially in Naples! Fruit has no place on an Italian pizza.

Spilling salt is seen as bad luck. Spilled salt bringing about misfortune is a common European superstition, probably related to salt’s high cost historically, and its use as a symbol of friendship. Romans often presented guests with salt first, to demonstrate a lasting friendship (perhaps because salt helps make foods last longer). The idea of spilled salt as a bad omen was only strengthened by the belief that Judas spilled salt at the Last Supper, as depicted by Leonardo da Vinci’s famous painting, and by the supposed Roman salting of Carthage after its defeat at the end of the Third Punic War (although if this happened, it would have been purely symbolic).

Spilling olive oil is another bad omen. Historically, olive oil was difficult to produce (just waiting for an olive tree to be productive takes years), and was a group effort. The work required, and olive oil’s nearly endless uses, made wasting it especially bad.

Gelato isn’t ice cream

Gelato and ice cream are two distinct dishes. Real gelato is made from milk, water, and sugar, and has less air and more flavoring, making it denser. Ice cream is fluffier, as it is made with cream and is airier. Sorbet is a bit closer to gelato, being made from water mixed with sugar and fruit flavoring.

Eat so as not to offend

Italians are understandably proud of their homemade cuisine. If someone gives you something to taste that they have made with their own hands, it’s highly offensive to refuse. If you’re not hungry, at least take a bite – nobody will be offended if you don’t finish food you’re given.

Maintain eye contact when toasting

When Italians cheer or make a toast, as in Germany, looking into their eyes is mandatory, as to do otherwise is a sign of betrayal. Toasting is also never done with water, a tradition said to have roots in the machiavellian renaissance, when being poisoned was a real danger among the nobility, who had to choose their drinking partners carefully!

Meals are social occasions

Our Italian colleagues were very careful in stressing just how important food is in their culture! If an Italian does not like someone, they may say, “We’ve never eaten together nor shared a meal,” which shows that they have shared little, and do not yet know each other well.

Gatherings, from family reunions to birthdays to holidays revolve around food. It is offensive to invite someone to a birthday, and have nothing to eat (dinners are the norm, but at least an aperitivo is seen as mandatory).

When possible, Italians eat together, especially for lunch and dinner. Cooking and eating are family activities, even once people have moved out of the house.

Try the time-limited local specialties

As elsewhere, some traditional foods are only eaten (and for sale) during certain times of year. Panettone, the Milanese take on fruitcake, is only served around Christmas. Colomba, a form of Panettone shaped like a dove, is saved for Easter. Frittele (Venetian fritters) and Crostoli (fried dough shaped in long twisted ribbons like the “Angel’s Wings” found in part of the Midwest) are a must during Carnival. Usually the time-limited treat is tied to a festival or the day of a city’s patron saint.

Italians deserve their friendly, extroverted reputation, and are more than happy to help guests explore their culture and its traditions, especially when it comes to food and drink. Italy has a strong hospitality culture, and food makes a strong part of that. With a few of the tips above, you’re sure to make a good impression! Want to explore Italian cuisine and culture for yourself? Our custom Italy tour packages are the perfect way to discover the delights of this magnificent country.

Born and raised in Wisconsin, Kevin lived in Estonia and Finland for several years, traveling widely through Central and Eastern Europe, before settling down in Berlin. Having studied the cultures, histories, and economics of the countries along the Baltic Sea for his Master’s degree, Kevin has the knowledge and experience to help you plan the perfect trip anywhere in the region, and also works as JayWay’s main writer and editor.